CRAWLEY FILMS YEARS

1948-1951

The portrait studio didn’t last very long. Stan likely wasn’t fond of doing the business part of running his own business, and might have been lured away by a chance to do more work behind the camera with Crawley Films. The company, launched by Budge and Judith Crawley in 1939, was now growing quickly, already an important player in the Canadian film industry. By all accounts, it was an exciting, happening place to work; a lot of very talented people were attracted by the creative, free-wheeling climate within the company, its growing acclaim, and the charismatic visionary himself, Budge.

I’m not sure at what point Stan was hired full-time, but in 1950, as Newfoundland became Canada’s tenth province, Stan did some shooting for a Crawleys’ film, Newfoundland Scene: a Tale of Outport Adventure, directed by Budge Crawley, sponsored by Imperial Oil. For the rest of Canada, this film would be an introduction to the new province’s rugged landscape, rich natural resources and unique culture.

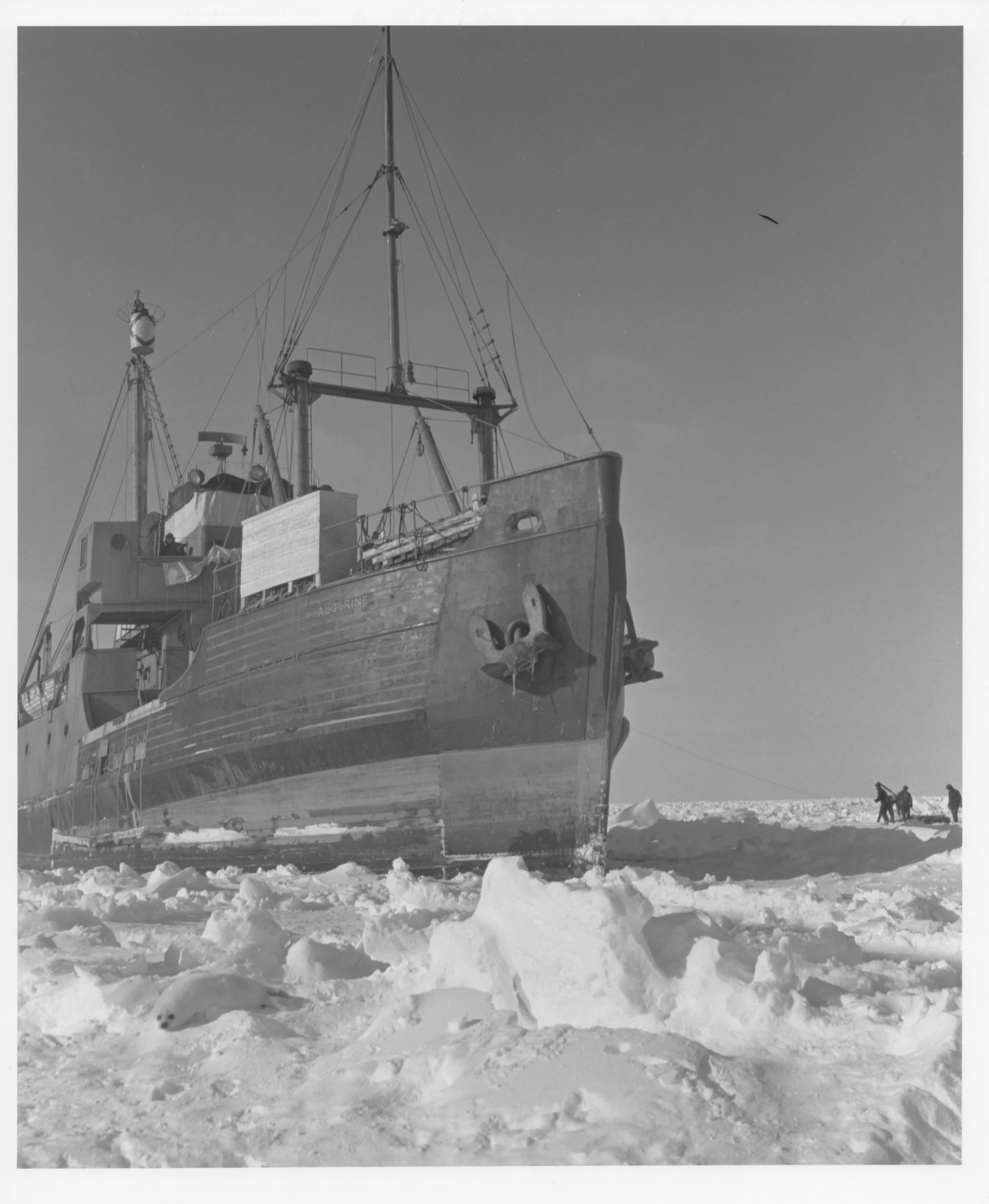

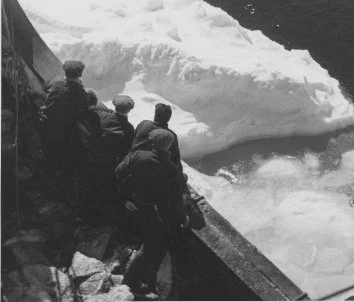

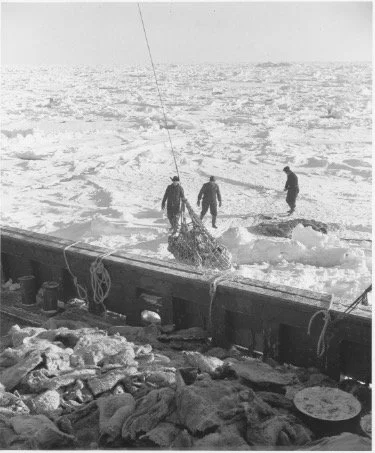

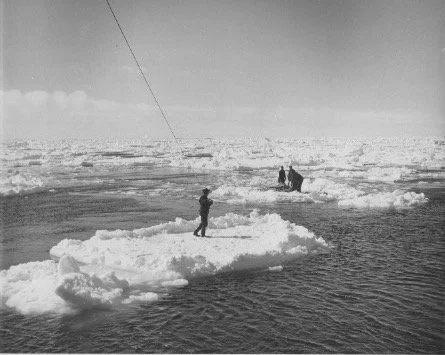

Much of the shooting would be done by Budge in the fall of that year, but in March, Stan went ahead to St. John’s to cover the Spring seal hunt. On the day after his 33rd birthday, he went onboard the M.S. Algerine, was a passenger for 19 days at sea, and came away with some truly remarkable footage.

Be thankful that the production stills he took are in black and white; the film was produced in living colour. His footage documented the sealers as they hunted for, and harvested the skins of the “White Coats”, or Harp Seal pups. The tally for pelts taken on that voyage totalled 24,000.

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) is a great source of Crawley Films material, including out-take footage shot by Stan on that trip. The content of one reel is described by archivist Steve Moore in great, disturbing detail. Stan apparently was so upset by what he was witnessing, he jumped into the fray, rescuing one pup and tucking it behind an ice floe, away from the eyes of the sealers.

LIbrary and Archives Canada

Credit: Photographer Anonymous,1950. LAC, Crawley Films Collection/MISA15545

In the first release of the finished film, viewers saw only glimpses and hints of the awful slaughter, but the undoubtedly controversial footage would later be eliminated completely from the film in 1962.

Stan returned to Ottawa, but travelled to Newfoundland again in the fall, assisting Budge with further filming. While Budge shot some incredible footage aboard a whaling vessel and in other locations, Stan was elsewhere on the island, filming day-to-day Newfoundland life.

Newfoundland Scene was first released in 1951. It won Film of the Year at the 1952 Canadian Film Awards, and was shown at the Edinburgh Festival the same year. If Stan wasn’t yet totally in love with this job by then, I would guess the attention this film received had him eager to continue his work for Crawley Films.

Widely in demand for many years, Newfoundland Scene was rereleased in 1972, featuring a fresh, up-to-date introduction delivered by actor Gordon Pinsent, who spoke of the many changes in the province in the intervening years. The newer version is available below. I think you will enjoy this Crawley classic. Watch for some amazing camera work by both Stan and Budge, whose whaling scenes were never removed from the film — be forewarned.

1951-1969

Over the next eighteen years, Stan worked on many motion picture projects with Crawleys’, hitting 150 by 1964, according to Canadian Cinematography magazine. He kept shooting until 1970.

In these years, it was clear to me that my father loved his work, though his frequent long absences were difficult for Jo, who juggled a full-time career and the raising of children. She shared this situation with many Crawley spouses, but the staff and their partners were a tight-knit group who frequently got together for social occasions. For Jo, a lifelong, bona fide party lover, this would have significantly helped take the sting out of being a film widow. I have been told Crawley parties leaned to the legendary, and in fact, I do remember a gathering, when I was very young, at the Crawleys’ estate in the Gatineau Hills. The kids were put to work stacking firewood in the afternoon, and offered pony rides. In the evening, things moved indoors, where the party really got underway. Tucked into a corner, watching the adults enjoy themselves, I was as amazed as anyone when the front door opened, and a man rode a horse into the living room of the Crawley home.

Besides the lively party scene, the quality of Dad’s letters home would have earned him some redemption for his absences. He would ask about life at home of course, and report on shooting progress, with promises he would soon be home. He also liked to make observations about the people he was with on location. I think this letter was written while he was in Yellowknife filming Top of a Continent in 1961. My parents wouldn’t mind me sharing this letter excerpt. Stan used terminology that is dated and thankfully out of use today, but the letter is a time capsule piece, so I have left it.

1958-1960

In 1958, the CBC hired Crawley Films to produce a TV series of 13 documentaries about life on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River. All episodes of Au Pays de Neufve-France were written by Pierre Perrault and directed by René Bonnière. As far as I know, Winter Crossing at L’Isle aux Coudres (La Traverse d’Hiver à L’Îsle aux Coudres) was the only episode filmed by Stan.

Perrault won the TV Information category at the 1959 Canadian Film Awards for this film.

If you only ever watch one Crawley production filmed by Stan Brede, this one would be a good choice. It will leave you with aching shoulders, and wondering how he ever captured such steady footage without dropping the camera into the frigid St. Lawrence River, or worse, falling in himself. I absolutely love this film — the cameraman was having a good time!

In 1959, ten years into his Crawley’s career, Stan was awarded membership to the Canadian Society of Cinematographers; a welcome acknowledgment of his contribution to the Canadian film scene of the day. Film credits bearing his name would now read “Stanley Brede CSC”.

In 1959-60, Crawley Films undertook a big project in collaboration with the CBC, the BBC, the Australian Broadcasting Commission and private investors. Crawleys would produce a one season crime drama series depicting life and work at an RCMP detachment in a small fictional Saskatchewan town. Every episode was a gripping, action-packed story of Mountie grit and heroic deeds; many of the plot lines were based on true stories. As a ten year-old sitting and watching the latest episode every week, I wasn’t a great fan of all the high crime in Shamattawa, but it became a very popular show, widely distributed, with an international following.

The RCMP series was a ground breaker, a big deal in the Canadian TV industry. Many talented cast and crew members of note came from across the world to work on it, and a big fancy new film studio was built in the Gatineau Hills north of Ottawa just for this project. 39 episodes were made—a lot to shoot in a year—and the schedule of a 30 minute episode every week, involving frequent travel to the location in Saskatchewan, was hectic. I remember my mother worrying about how tired Stan seemed in his role of Director of Photography for many of the episodes.

If you enjoy this classic fifties style of TV crime and action shows, you might get a kick out of watching some of the episodes available online. Here’s a sample.

Early sixties

The hectic shooting schedule did not slow down when the RCMP series ended.

On Monday nights in 1961-63, CBC TV aired a series, Camera Canada, highlighting some episodes in modern Canadian history. One of the programs, produced by Crawley’s and directed by René Bonnière, was The Annanacks, about an Inuit community in Northern Québec. Stan shared shooting responsibilities with the highly respected cinematographer Chris Chapman, and between them, they captured some wonderful footage, indoors and out.

I remember Crawleys’ bringing some of the Annanack family members south and hosting them around Ottawa and Montréal for a few days. One event was a loud and lively square dance which my childhood memory tells me lived up up to Crawley party standards, and everyone had a great time.

1964

1964 was a good year for Stan, as mentioned in the industry magazine. He won Best Colour Cinematography at the Canadian Film Awards, for Brampton Builds a Car, directed by Jim Turpie, and worked on some other noteworthy film projects.

The Luck of Ginger Coffey stands out from that year as one of Crawleys’ feature film projects — a new thing for the company. Directed by Irvin Kershner (of The Empire Strikes Back fame), and starring Robert Shaw (from Jaws), it was shot in the Crawley studios, and in Montréal. Stan isn’t in the credits, but was in fact, brought in to shoot exteriors in Montréal. From the notes of my brother Mike comes the story that Kershner told Dad he was good enough to do cinema work in Hollywood. Was there an actual offer? Mike didn’t know, but apparently Stan refused the idea, and Jo was not pleased. This sounds about right. Mike’s notes do not omit the fact that he got to be an extra in a courtroom scene, and sat next to Kershner’s wife, Mary Ure for his moment of fame.

The Luck of Ginger Coffey won Best Theatrical Feature at the 1965 Canadian Film Awards.

1965

1965 also saw the production of The Perpetual Harvest, directed by Peter Cock, sponsored by MacMillan Bloedel. It sang the praises of BC’s forest industry for providing the world with so many useful products, and for its resource management and reforestation efforts. Whatever we might think now of the forestry practices of the day, it seems it was a very fine film, and Crawley films won quite a few awards for it:

1966: Canadian Film Awards; Best Documentary

1966: International Film and Television Festival of New York; Best Photography; Stan Brede, Chris Chapman, Directors of Photography

1967: Canon Film Awards; Sales and Promotional Films

1969: Canadian Forestry Film Festival; category unknown

1969: International Festival of Fire Control Films; category unknown

LATE SIXTIES

Stan continued his work behind the camera for only a few more years after this. We hadn’t yet understood that he was suffering from alcohol addiction, but over a short time, it became apparent to us at home, and to his colleagues. He continued working for awhile, and sought treatment with the support of the family and his “other family” at Crawley Films. Ironically, part of his treatment included being required to watch a film, Face of an Addict, including his own name rolling by in the credits. Somehow, we all found this funny.

The last film I remember Stan working on was the House of Seagram sponsored 1969 Canadian Open golf tournament, The Sun Don’t Shine on the Same Dawg’s Back All the Time. The title was a colourful quote from 2nd place winner that year, Sam Snead — and in retrospect, an apt description of Stan’s personal situation. Dad was crazy for golf, and really enjoyed filming tournaments. I drove to Montréal that weekend to watch some play, and was able to chat with him for a just a couple of minutes in between filming.

In the spring of 1970, Stan died at the age of 53. When he should have had quite a few promising years left to make his mark in the film industry, he was robbed of the chance, as so many addicts lose their chances.

He wasn’t a person who talked about himself much, and his typical response to his situation would have been a simple and pragmatic,“That’s life”.

My brother started cataloguing the films Stan had worked on in his life, and I picked up the job after Mike’s death. Between us, we were able to come up with 146 titles, thanks to a list our mother had kept, and various internet sources. Not every title hints at cinematic magic of course, but there were some truly exceptional films that Stan played a part in, of which he was very proud.

After Dad’s death, Crawley’s commissioned the then well-established artist Art Price to create a commemorative plaque in his honour—the same Art Price who had given him a beautiful carving as payment for his photographic services, after the war. I believe the plaque remained in the foyer at 19 Fairmont Ave for as long as the Crawley Films studio was located there. I don’t know where it is now, but wish I did.